What is a “Personal VPN”

As I’ll be using it in this article, “personal VPN” or just simply “VPN” will refer to VPN (Virtual Private Network) services for the masses: Nord VPN, ExpressVPN, Private Internet Access, etc.

These VPN services allow you to tunnel your internet activities for your devices to another location in the world; a selection of POPs (Points of presence) is offered by the VPN provider. This can be useful since most IP addresses have geolocation data associated with them which internet services can use to know the city a user is connecting from.

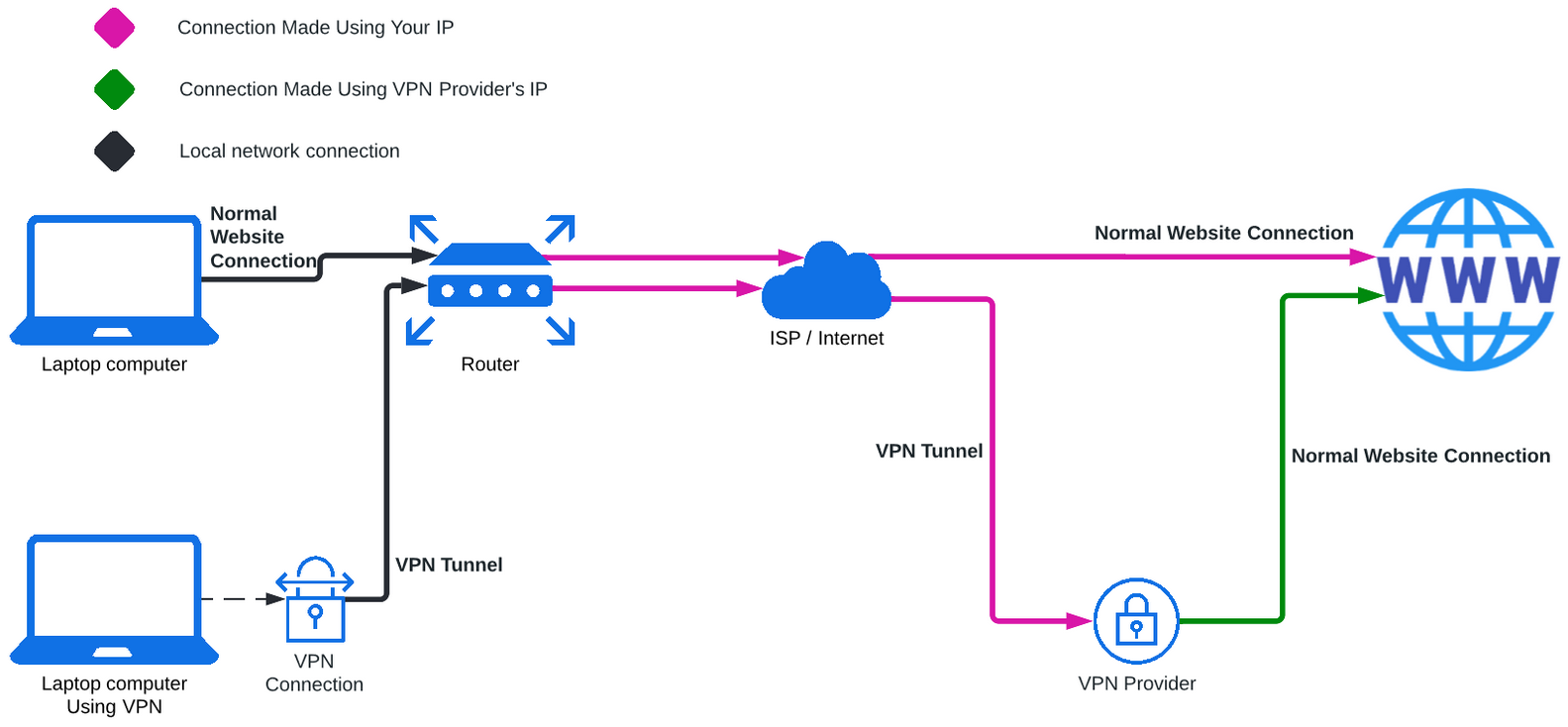

In order to demystify this further, here’s a simple network diagram using the example of a website connection. Two devices are shown on the same network connected to the same website. One is using a VPN service while the other is not. I have color coded the connection arrows based on IP address.

For the device without the VPN: Your ISP (Internet Service Provider) will see you connecting to a website. The website will see a connection coming from your public IP (issued by your ISP). The website will also know any other data you give it such as what page on that website you are visiting, who you are logged in as, etc. The website will also have the capability to know other metadata about the connection such as your approximate location (based on the IP geolocation data), your browser, your session (it will remember you based on cookies your browser has stored), etc.

For the device with the VPN everything is the same from the first scenario except for the following: Your ISP (Internet Service Provider) sees you connect to a VPN provider, but can no longer see what website you are connecting to or even what ports / protocols you’re connecting to aside from the VPN service. The website no longer sees your ISP issued IP address, and instead can only see the IP address issued by the VPN provider. The VPN provider can additionally now see everything the ISP saw before plus potentially being able to see which device you are connected with, depending on the VPN connection method.

For the VPN connected device everything else stays the same, so if you have cookies saved from your previous sessions or you login to the website, the website will know who you are and can correlate other IPs it has seen you use.

By using the VPN, the VPN provider effectively becomes your ISP. This means that the geolocation data is now associated with the physical location of the VPN POP (Point of Presence).

Why would you want a VPN?

Let’s start with some common legitimate use cases for a VPN.

Public Wi-Fi

So you need to use public Wi-Fi and don’t want the risks associated with connecting your device.

There are primarily two broad risks associated with public Wi-Fi:

Risk 1: Somebody sniffs your traffic

The impact of this is that at least they will know what you are communicating with (what server IP and/or Domain you are connected to). This could reveal what apps you have installed on your phone or laptop, what site you are visiting or browsing, etc. This also allows the attacker to view any unencrypted communications. This is NOT limited to browser communications, I have seen many a mobile app send requests with sensitive data in plaintext.

In general, if you are using https for website traffic you should be OK, but a good VPN in “full tunnel” mode will reduce this risk.

Risk 2: Somebody attacks your device

- Exploiting Vulnerabilities:

- Your device has services running on it which might be able to be exploited or attacked by another device on the local network. If your device and all applications are up-to-date and still have support for security patches, you should be OK.

- Man-in-the-Middle:

- If as mentioned above your device has any clear-text communications (browser sessions not using https, or apps which you may not be aware are communicating using unencrypted protocols) then you run the risk of an attacker modifying the communications. This means if you’re browsing an http site, an attacker can theoretically modify the site and links displayed to you in addition to viewing all of the data.

When considering the defense against both of these risks, I would recommend a “full tunnel” VPN versus a VPN which only uses split tunneling. So-called “full tunnel” VPNs will only allow communication out to the VPN service. Many VPN providers can do both, so review your settings.

ISP Problems or Concerns

If your ISP (Internet Service Provider) is limiting your access to certain sites and services, slowing down video and other media, or outright selling your data to third parties or using your activity to price select, a good VPN provider probably won’t be much worse. In this circumstance a VPN service might help, assuming that the ISP doesn’t also have bandwidth restrictions or blacklists against VPN services.

Geolocation Concerns

If you have mild concerns around a website or service knowing your physical location, a VPN service should work fine. Let’s be clear though: A VPN is not the best solution for this if you have any legitimate concerns about OPSEC or safety, but it is easy, convenient, and generally fast enough to stream media or play video games online.

If it is slightly more important to you that the site or service not know anything about your true location, make sure you are aware of any other mechanisms that could be used to correlate you with your true location. Such mechanisms might include cookies, browser fingerprinting, location permissions, etc. A fresh Incognito mode in your browser is generally going to fool most services but be aware it’s not a bulletproof solution.

If you’re using the VPN for streaming movies from a service like Netflix which controls content by country, keep in mind most VPN POPs are easily identified as VPN services and may be blocked.

Censorship concerns*

I have an asterisk here because this is where it gets into more of a need for OPSEC. Do not rely on a VPN for anything where you have legitimate concerns about your own safety.

If you’re sure what you are doing is legal in all countries your traffic is traversing (your network, the VPN service network, the destination network), and you won’t be retaliated against, then you can use a VPN to gain access to portions of the internet which may not otherwise be available to the country you’re connecting from. For example if you are in a country which is blocked by a certain company, but you would like to view their website, a VPN might help with this.

Anonymity*

Another asterisk here, since once again if you’re truly concerned about anonymity and have any concerns for your safety, a VPN is probably the wrong choice. One glaring limitation to anonymity in this scenario is your VPN provider still knows who you are and where you’re going.

By using a VPN, your traffic is blended with the traffic from other users. I’ll stress that this is the only way that a VPN helpfully contributes to anonymity online. This does not mean your browser plugins, cookies, usernames, and other data are no longer unique to you.

Again, be sure you know the nuances and understand other ways you can be tracked online and correlated with your other identities before you start using a VPN for this.

Do not confuse Anonymity with Privacy. Any sites or services will still see what you are posting or doing on their website.

Reasons you shouldn’t use a VPN

You don’t know what it is

Often people will ask me if a VPN will help them to stay more secure online. They do not have any specific goals or use cases when asking this, so of course the answer is “it depends, but probably no.”

Look for a solution to a problem, not problems for your solution.

You generally want to prevent being hacked

A VPN is not the end-all be-all security solution. It offers moderately better protection in some circumstances, but also offers virtually no security benefits which would prevent the standard user from being “hacked.”

You have a high-level threat model for your privacy or anonymity

A VPN is probably not the best choice if you could face serious consequences if something goes wrong with the use-case you have for a VPN. There are plenty of good (free) solutions out there which provide higher levels of privacy and anonymity in addition to covering the other use cases for a VPN which are listed above.

Some VPNs may sell or disclose your data

This could include sale to third parties, release of your data to governments, or questionable privacy practices which might lead to accidental disclosure.

Free VPNs definitely sell user data, and some are profitable. Most reputable paid VPNs should not sell your data, but that could change at any time without notice depending on the privacy policy language.

You can use tosdr.org as a resource to get the “sparknotes” version by looking up the VPN provider’s website. Context is important and may not be apparent depending on which sections of the privacy policy apply to the website itself versus the VPN services. That being said, I’ve included some examples (at random and in no particular order) of what tosdr.org can provide below. (I am not saying these are bad or good):

It also pays to keep an eye on the news (consider past history of a VPN provider). There have been cases where VPN providers have released customer logs to law enforcement, despite having a “no logs” policy. So take those claims with a grain of salt.

This is speculation but worth noting: Since most VPN providers are B2C (business to consumer), there’s a chance they may not be as concerned about lawsuits from customers for not following the privacy practices they claim. Also, most criminals who have their data released by VPN providers are probably not in a position to sue.

Kape Technologies acquired some VPN providers like Private Internet Access in 2019, ExpressVPN in 2021, which raised some eyebrows as the new parent company was not known for good privacy practices (previously it was known for owning products related to advertising which fell victim to adware and malware abuse).

Alternatives

As promised, here are a couple of alternatives to using a paid VPN service

TOR

Currently, nothing beats TOR for the highest level of privacy and anonymity while engaging with the open internet. For anyone with a high-level threat model that doesn’t mind slow bandwidth, the TOR project is a great start: https://www.torproject.org/ They offer a browser client which is hardened and can connect to the TOR network. They also offer a few android / iOS apps as well which are built to leverage the TOR network. For anyone with serious safety concerns, I would also recommend a dedicated operating system like Tails https://tails.boum.org/

With TOR, you are using onion routing. Put simply, there are at least three other volunteer computers which will help route your traffic (the “onion”). These computers are ideally decided at random using a list of computers. Each computer that manages your traffic has a key to unlock one layer of the onion. The first computer, (we’ll call it computer 1), knows exactly who you are, but not where you are going. It gets the full onion but doesn’t know how many layers there are. Computer 1 peels off a layer which tells it where the next computer is located. This repeats until Computer N (the last computer) peels off the final layer and sends your traffic to the destination, but has no clue where the traffic came from originally. This process is reversed when traffic is sent back to you from your destination. The key exchange to establish the connection works much the same way.

Some caveats: Like with a VPN, make sure you understand how it works (at least a little) so you can understand exactly how it protects you (and how it doesn’t) before you rely on it. Also, a lot of sites block TOR, which is unfortunate but understandable.

Your own VPN

TOR is usually the best option for a privacy use case but it can be slow. If you need a VPN for another use case and have the technical skills, you can create your own VPN (for “free” or for low cost). This could be useful in some of the specific circumstances already mentioned, but you will still face a lot of the privacy and anonymity downsides since your choices are probably limited to hosting the VPN at home or in the cloud, and even if you don’t keep logs, your ISP or cloud provider probably do. Anonymity for your own VPN is generally worse than a good paid VPN service unless you’re also hosting a TOR exit node or make the VPN available to the general public (which may expose you to additional risks).